About Kernel Symbol Table, Compilation, and more

Date:

This week I was planning on talking about Device Mocking with KUnit, as I’m currently working on my first unit test for a physical device, the AMDGPU Radeon RX5700. I would introduce you to the Kernel Unit Testing Framework (KUnit), how it works, how to mock devices with it, and why it is so great to write tests.

But, my week was pretty more interesting due to a limitation on the KUnit Framework. This got me thinking about the Kernel Symbol Table and compilation for a while. So, I decided to write about it this week.

The Problem

When starting the GSoC project, my fellow colleagues and I ran straight into a problem with the use of KUnit on the AMDGPU stack.

We would create a simple test, just like this one:

#include <kunit/test.h>

#include "inc/bw_fixed.h"

static void abs_i64_test(struct kunit *test)

{

KUNIT_EXPECT_EQ(test, 0ULL, abs_i64(0LL));

/* Argument type limits */

KUNIT_EXPECT_EQ(test, (uint64_t)MAX_I64, abs_i64(MAX_I64));

KUNIT_EXPECT_EQ(test, (uint64_t)MAX_I64 + 1, abs_i64(MIN_I64));

}

static struct kunit_case bw_fixed_test_cases[] = {

KUNIT_CASE(abs_i64_test),

{ }

};

static struct kunit_suite bw_fixed_test_suite = {

.name = "dml_calcs_bw_fixed",

.test_cases = bw_fixed_test_cases,

};

kunit_test_suite(bw_fixed_test_suite);

Ok, pretty simple test: just checking the boundary values for a function that returns the absolute value of a 64-bit integer. Nothing could go wrong…

And, at first, running the kunit-tool everything would go fine. But, if we tried to compile the test as a module, we would get a linking error:

Multiple definitions of 'init_module'/'cleanup_module' at kunit_test_suites().

This looks like a simple error, but if we think further this is a matter of kernel symbols and linking. So, let’s hop on and understand the basics of kernel symbols and linking. Finally, I will tell the end of this KUnit tell.

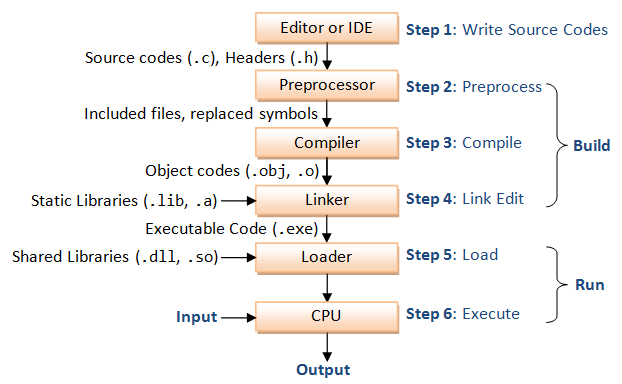

The Stages of Compilation

First, it is important to understand the stages of the compilation of a C program. If you’re a C-veteran, you can skip this section. But if you are starting in the C-programming world recently (or maybe just used to run make without thinking further), let’s understand a bit more about the compilation process for C programs - basically any compiled language.

The first stage of compilation is preprocessing. The preprocessor expands the included files - a.k.a. .h, expands the macros, and removes the comments. Basically, the preprocessor obeys to the directives, that is, the commands that begin with #.

The second stage of compilation is compiling. The compiling stage takes the preprocessor’s output and produces either assembly code or an object file as output. The object code contains the binary machine code that is generated from compiling the C source.

Then, we got to the linking stage. Linking takes one or more object files and produces the product of the final compilation. This output can be a shared library or an executable.

For our problem, the linking stage is the interesting one. In this stage, the linker links all the object files by replacing the references to undefined symbols with the appropriate addresses. So, at this stage, we get the missing definitions or multiple definitions errors.

When ld (or lld for those at the clang community), tells us that there are missing definitions, it means that either the definitions don’t exist, or that the object files or libraries where they reside are not provided to the linker. For the multiple definition errors, the linker is telling us that the same symbol was defined in two different object files or libraries.

So, going back to our error, we now know that:

- The linker generates this error.

- We are defining the

init_module()/cleanup_module()twice.

But, if you check the code, there is no duplicate of either of those functions. 🤔

Ok, now, let’s take a look at the kernel symbol table.

Kernel Symbols Table

So, we keep talking about symbols. But now, we need to understand which symbols are visible and available to our module and which aren’t.

We can think of the kernel symbols in three levels of visibility:

- static: visible only inside their compilation unit.

- external: potentially visible to any other code built into the kernel.

- exported: visible and available to any loadable module.

So, by quoting the book Linux Kernel Development (3nd ed.), p. 348:

When modules are loaded, they are dynamically linked into the kernel. As with userspace, dynamically linked binaries can call only into external functions explicitly exported for use. In the kernel, this is handled via special directive called

EXPORT_SYMBOL()andEXPORT_SYMBOL_GPL(). Export functions are available for use by modules. Functions not exported cannot be invoked from modules. The linking and invoking rules are much more stringent for modules than code in the core kernel image. Core code can call any nonstatic interface in the kernel because all core source files are linked into a single base image. Exported symbols, of course, must be nonstatic, too. The set of exported kernel symbols are known as the exported kernel interfaces.

So, at this point, you can already get this statement, as you already understand about linking ;)

The kernel symbol table can be pretty important in debugging and you can check the list of symbols in a module with the nm command. Moreover, sometimes you want more than just the symbols from a module, but the symbols from the whole kernel. In this case, you can check the /proc/kallsyms file: it contains symbols of dynamically loaded modules as well as symbols from static code.

Also, during a kernel build, a file named Module.symvers will be generated. This file contains all exported symbols from the kernel and compiled modules. For each symbol, the corresponding CRC value, export type, and namespace are also stored.

Building an out-of-tree module is not trivial, and you can check the kbuild docs here, to understand more about symbols, how to install modules, and more.

Now, you have all the pieces needed to crack this puzzle. But I only gave you separate pieces of this problem. It’s time to bring these pieces together.

How to solve this linking problem?

Let’s go back to the linking error we got at the test:

Multiple definitions of 'init_module'/'cleanup_module' at kunit_test_suites().

So, first, we need to understand how we are defining init_module multiple times. The first definition is at kunit_test_suites(). So, when building a KUnit test as a module, KUnit creates brand new module_init/exit_module functions.

But, think for a while with me… The amdgpu module, linked with our test, already defines a module_init function for the graphics module.

FYI: the

module_initis the module entry point when the module is loaded.

So, we have figured out the problem! We have one init_module at kunit_test_suites() and other init_module at amdgpu entry point, which is amdgpu_drv.c. And, as they are linked together, we have a linking problem!

And, how can we solve this problem?

Solutions inside the tests

-

Adding

EXPORT_SYMBOLto all tested functionsGoing back to the idea of the Kernel Symbol Table, we can load the

amdgpumodule and expose all the tested functions to any loadable module by addingEXPORT_SYMBOL. Then, we can compile the test module independently - that said, outside theamdgpumodule - and loaded separately.It feels like an easy fix, right? Not exactly! This would pollute the symbol namespace from the

amdgpumodule and also pollute the code. Polluting the code means more work to maintain and work with the code. So, this is not a good idea. -

Incorporating the tests into the driver stack

Another idea is to call the tests inside the driver stack. So, inside the AMDGPU’s

init_modulefunction, we can call the KUnit’s private suite execution function and run the tests when theamdgpumodule is loaded.It is the strategy that some drivers, such as thunderbolt, were using. But, this introduces some incompatibilities with the KUnit tooling, as it makes it impossible to use the great

kunit-tooland also doesn’t scale pretty well. If I want to have multiple modules with tests for a single driver, it would require the use of many#ifdefguards and the creation of awful init functions in multiple files.Creating a test should be simple: not a huge structure with preprocessor directives and multiple files.

A better solution: changing how KUnit calls modules

The previous solutions were a workaround for the real problem: KUnit was stealing module_init from other modules. For built-in tests, the kunit_test_suite() macro adds a list of suites in the .kunit_test_suites linker section. However, a module_init() function is used for kernel modules to run the test suites.

So, after some discussion on the KUnit Mailing List, Jeremy Kerr unified the module and non-module KUnit init formats. David Gow submitted a patch from him removing the KUnit-defined module inits, and instead parsing the KUnit tests from their own section in the module.

Now, the array of struct kunit_suite * will be placed in the .kunit_test_suites ELF section and the tests will run on the module load.

You can check the version 4 of this patchset.

Having this structure will make our work on GSoC much easier, and much cleaner! Huge thanks to all KUnit folks working on this great framework!

Getting this problem is not trivial! When it comes to compilation, linking, and, symbols, many CS students get pretty confused. In contrast, this is a pretty poetic part of computation: seeing these high-level symbols becoming simple assembly instructions and thinking about memory stacks.

If you are feeling a bit confused over this, I hugely recommend the Tanenbaum books and also Linux Kernel Development by Robert Love. Although Tanenbaum doesn’t write specifically about compilation, the knowledge of Compute Architecture and Operational Systems is fundamental to understanding the idea of running binaries on a machine.